Editor's Choice

The Rise of English Opera

Erin Pearson

Eighteenth Century Drama focuses on British theatre 1737-1824; the introduction of the Licensing Act of 1737 meant that newly written plays required a licence from the Lord Chamberlain’s office in order to be performed. One of the conditions of the Licensing Act of 1737 was that ‘serious’ plays could only be performed at certain theatres that had been granted patents – and nothing was considered more serious than Opera. Held in high regard and traditionally focusing on the tragedies and successes of Gods, deities, monarchs, figures from antiquity and, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, always performed in Italian, Opera was the most elitist form of drama.

A hidden celebrity of Eighteenth Century Drama is George Frederick Handel born in Saxony in 1685, the composer spent his early life in Europe prior to moving to London in 1710 (and moving into Brooke Street, London in 1723 – which would become the home of Jimi Hendrix in the late 1960s). Handel began his career in Britain at the Queen’s Theatre (known as the King’s from the accession of King George I) – which specialised in the performance of Opera.

Over the course of his career Handel would begin to change attitudes towards, and the style of, Opera; while he did compose many archetypal Operas he began to develop the Oratorio style. The Oratorio is less strict in form than Opera as Handel lacked classical training in writing and composing for chorus and so began favouring choruses in English rather than Italian.

One of Handel’s best known Oratorios was Samson in which the use of choruses peaked. The success of these performances in English meant that Handel began to produce them more regularly; of course a sensible business decision and the increased use of this style began to change the perception of opera from the exclusive, classical Italian style and allowed for the growth of a burgeoning English opera scene.

See documents related to Handel here.

A Family Business

British theatre during the eighteenth century was often a family affair. The stage frequently saw husband and wife, as well as cross generational casts. However, none were more prolific than the great Kemble family.

Actor Roger Kemble met his wife Sarah Ward after joining her father’s acting company. Together they had 12 children who, between them, ruled the British stage for decades. The most famous of these children were Sarah, who would perform under her married name Siddons; John Phillip; Charles; Stephen and Elizabeth. All three sons married actresses, John marrying Priscilla Hopkins Brereton, Charles marrying Maria Theresa and Stephen marrying Elizabeth Satchell, who together had an actor son Henry.

After an initial failed engagement at Drury Lane, Sarah built a successful career in Bath. However, her return to London in October 1782 was a triumphant one, seeing her garner rave reviews for her performance as Isabella in Isabella, or, The Fatal Marriage.

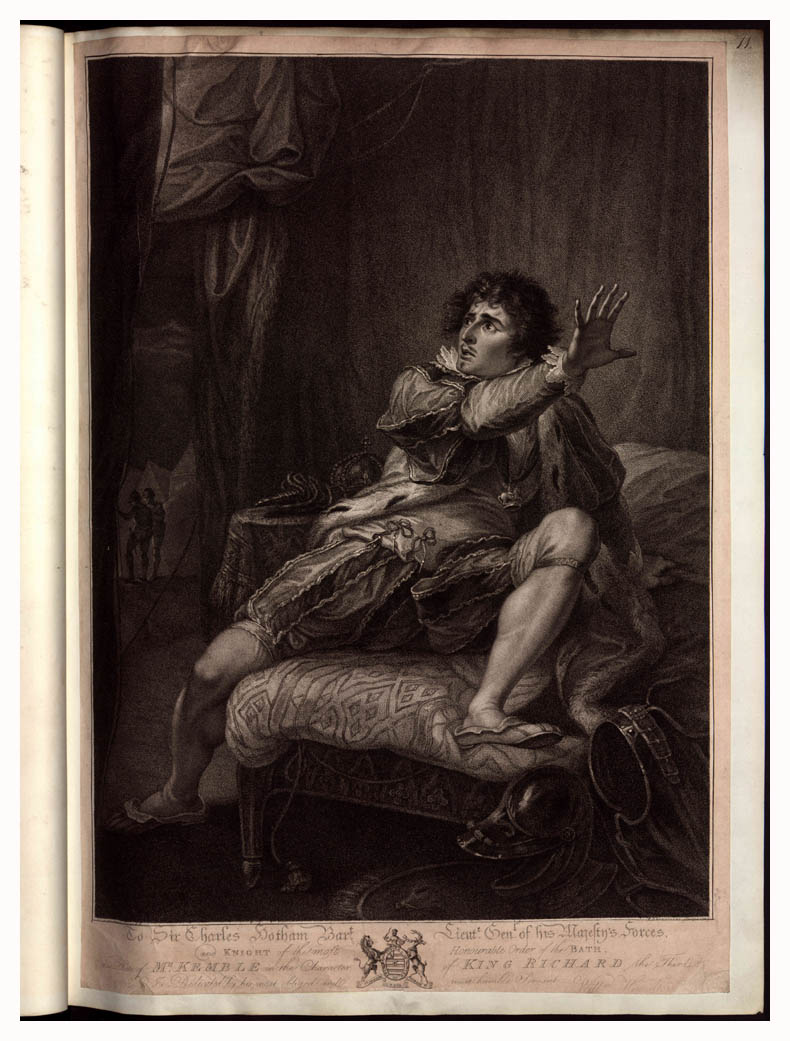

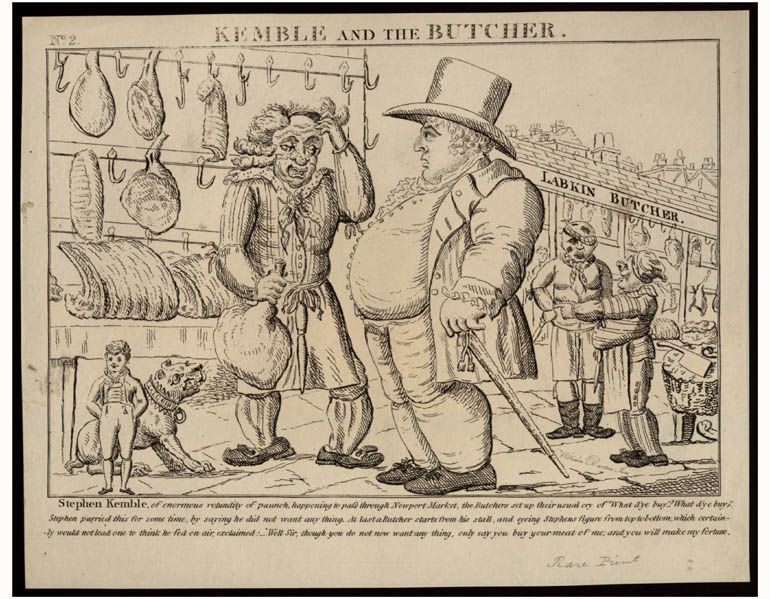

John Phillip, having built a reputation performing at provincial theatres, joined his sister at Drury Lane in 1783. Their brother Stephen had recently debuted at Covent Garden – to not spectacular reviews – but John’s first London performance, as Hamlet, ignited considerable conversation amongst critics.

John played the title role in Edward the Black Prince on 20 October 1783, in which his sister Elizabeth acted as Mariana. Success arrived when he appeared, upon royal request, with Sarah as Mr and Mrs Beverley in The Gamester. The reaction was extremely positive with the Public Advertiser proclaiming "as many tears as ever were shed in a theatre on one evening". By 1788 John Phillip was the manager of Drury Lane, Sarah was a cultural icon and the preeminent actress of the age and Stephen had found great success in managing provincial theatres.

Charles arrived on the London stage in 1794, playing many secondary parts to John and Sarah’s leads, but eventually building independent fame. In 1802, both Sarah and John left Drury Lane, with John taking up management of Covent Garden Theatre. The Kemble’s time at Covent Garden was mixed. The fire in 1808 led to severe financial difficulties and the Old Price Riots did nothing to alleviate this strain. Nevertheless, Sarah’s farewell performance in 1812 was considered one of the greatest of all time after she gave an eight minute speech to rapturous applause.

The dynasty continued with the next generation of Kemble’s also feeling the lure of the stage. Sarah’s eldest son Henry became an actor and playwright, Charles and Maria Theresa’s daughters Fanny and Adelaide became an actress and an opera singer and Stephen’s and Elizabeth’s son, also called Henry, became an actor too.

Through The London Stage Database, users can explore in much greater detail the colourful stories off all members of the Kemble family, taken from the original images of the nine volumes of The London Stage.

The Irishman in London

A large amount of the plays contained in Eighteenth Century Drama grapple with domestic life, featuring rites of passage within a family such as courtship and providing entertainment by dramatising or infusing humor into everyday affairs. Plays of this type commonly featured servants and, less often, slaves, who played background roles yet were necessary in order to depict a more complete view of the wealthy and comfortable English family.

William Macready, probably known better for his acting than his authorship, penned and acted in a popular farce titled The Irishman in London; or, the Happy African, which was innovative and, even radical, in its departure from conventional pieces focused on the English household. In this play, the stereotypical characters of Murtock, an Irish servant and Cubba, an African slave, are promoted to the role of protagonists while still maintaining the qualities which were frequently assigned to characters of their respective backgrounds in other plays. Murtock was stubborn and relentless in his loyalty to, and longing for, Ireland, while Cubba was a descendant of African royalty – her relocation through slavery can be read as that of a 'noble savage' on the path to civilisation. Each of their speech patterns followed those of stock characters – Cubba spoke in extremely broken English, which is sometimes hard to follow, while Murtock used phrases which were perceived by other authors to mark out an Irishman, such as “to be sure” and “arrah”. The relationship, a friendship with eventual romantic feelings between the two, which over the course of the play challenged racial barriers, was juxtaposed with the potential marriage of Cubba’s mistress Caroline to a man she did not love.

Macready’s farce, although a departure from traditional storylines and conventional methods of exploring English identity, still demonstrated contemporary approaches to race and slavery at the time. Despite the extraordinary amount of focus directed on a slave, the play does not seemingly offer any criticism on the concept of slavery itself. On the contrary, it seems to promote a prevalent idea at the time that slavery was a symbiotic relationship which markedly improved the lives of slaves from those they had at home. Similarly, despite the play giving a central role to Cubba, she essentially relinquished the agency afforded to her throughout the play and re-assumed her place in the traditional racial hierarchy. Both Murtock and Cubba eventually acknowledge racial realities which mean that a white man, even if Irish, should not have married a black woman. Murtock bemoans the fact that a fellow “that advertises to whiten a lady’s hands and faces” could not be found for Cubba.

The Irishman in London; or, The Happy African is striking due to its original plot and its willingness to grapple with issues of identity, race and 'otherness' – subjects which, in drama, were more frequently looked at in the context of empire and exotic lands. Macready’s play was different – it explored these issues within a house in London through the lens of subaltern protagonists, bringing those on the fringes of society to the fore.